Comic Theory 101: Seeing Rhymes

This article was originally written for my periodic column at the online magazine Comixtalk in June 2006.

As you probably know, I’ve been expounding on a theory that sequential images can actually be called a language — a visual language — which emerges along with text in comics. In this article, I’m going to take a diversion from my usual heavy theory to look at some ways in which we can apply some of the ideas of visual language in practice.

Not all things from the verbal realm can apply to the visual. For instance, it would be very difficult (but not impossible) to have homophones in visual form (words that sound the same with different meanings). However, one area that is quite possible lies in rhyming.

As most everyone knows, rhyming is when the sounds of one word correspond to the sounds of another word or words: bear and pear; hat, mat, and bat; manga and conga.

While it might create a different feeling, we could hypothetically say that rhyming in the visual domain also establishes a correspondence between two different visual parts. Of course, the visual form can do this in many ways. On a small scale, rhyming is available to the contents of individual panels.

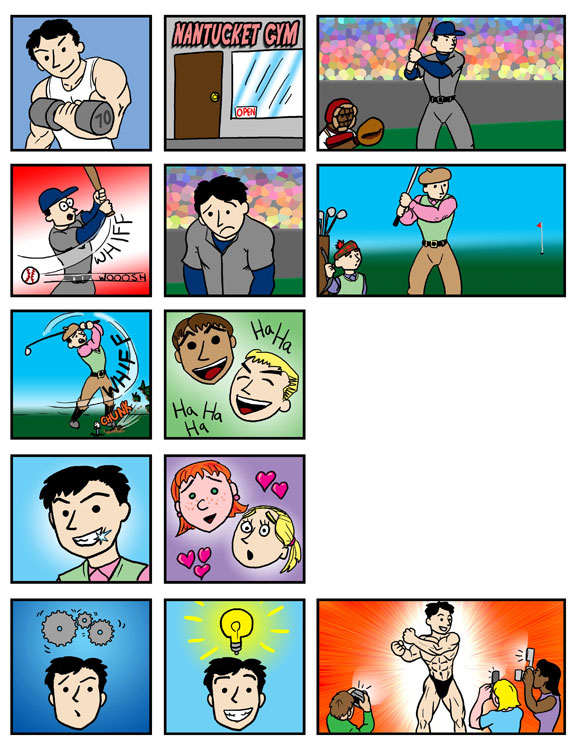

For example, these two panels are nearly identical, with only a slight change in them:

They aren’t the same panel, but the change is enough that one might associate the content of one with the other. Essentially, this correspondence between the composition and content of images creates a visual rhyme. Here’s another one:

In storytelling, visual rhyming creates interesting juxtapositions of content, like in panels that recur throughout a story with only slight changes. Visual rhyming can also create a smooth transition from one scene to another. For instance, shifting from an airport to an office using a panel of a plane propeller and a panel of a fan.

The visual form also allows for a type of rhyming that is unavailable to auditory poetry. This correspondence comes on a larger level of page layout. I would consider the following layouts to “rhyme” with each other on a large scale, along with the internal rhyming of some of the internal content:

Of course, in order for this large-scale correspondence to work, the page layouts need to be novel enough to be distinct and recognized as such. For instance, three panel strips with square panels or six panel grids are not unique enough to evoke the recognition that rhyming takes place.

With layouts (and possibly image content), reverse rhyming is also possible. Here, the layout of one page is the exact reverse of another one. This technique was used quite famously in Alan Moore’s Watchmen, to visually mimic the characteristics of a Rorschach test.

Theoretically speaking, rhyming isn’t the most interesting of topics, and I can understand if people might want to quibble with the very idea of visual rhyming. However, we can put this theorizing to use in a variety of interesting and fun ways, like those discussed above. Or, we can borrow some contexts from verbal expression.

Naturally, rhyming of any sort doesn’t truly become interesting until it’s used in particular patterns. If random words strewn about in sentences just happen to rhyme, most of the time we don’t notice it, but when its put into a particular pattern, then it becomes apparent.

Indeed, rhyming usually stays out of prose works, but for poetry it is often essential. Personally, I’m a big fan of writing poetry, especially traditional poetry with structure that needs to be followed. To me, showing your skill at working within boundaries is often even more impressive than breaking or making them up as you go. Being able to stick to the rhyming structure and meter of say a sonnet while saying something substantial demonstrates how skilled one’s intuitions of the English language have been honed.

As far as I know though, no one has really established parameters like this for “visual language poetry.” Some attempts have been made by people like Derik Badman to make visual language haiku and pantoum, but by and large no conventionalized tropes have been established. To me, this seems like a fertile and under-explored realm for experimentation, which I’ll continue to explore in my next column.

So, to get the ball rolling, I here offer a visual language poem in one of my favorite poetic styles (and encourage others to follow up with their own!). Care to guess what it is?

Comments