Comics in Education

Comics in Education

Comics have long been shown to be an effective tool for education and instruction. I’ve helped create comics for use in education, have collaborated on research about this topic, and teach classes for people to make their own educational comics. Below, I share some insights and distinctions from our research, and provide a few resources.

Definitions

Though many are in support of “comics in education”, this phrase can actually mean a few different things. One meaning is for “comics” to be used in the classroom, like the publications that exist and convey various themes like superheroes, manga, etc. Here, comics are used as reading material for literature, as context for learning languages, or as examples to sponsor discussion, such as reading a comic that takes place during a war as a prompt to discuss that time in history.

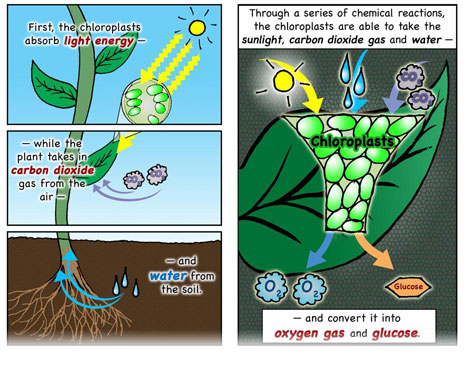

A different use of “comics” involves using sequential images combined with text as a way to convey educational material. This might be called using the “comic medium” to educate. I would call this the use of “visual language” and writing, whether it’s tied to the social notion of comics or not. In this case, textbooks or educational materials might use sequential images to communicate. This often happens in the growing use of data comics, graphic medicine, or science comics.

These are both valid uses for comics in education, and studies have shown that both of them can be effective for learning. However, it’s important to distinguish which type of use we’re talking about when discussing “comics in education.”

Comprehension processes

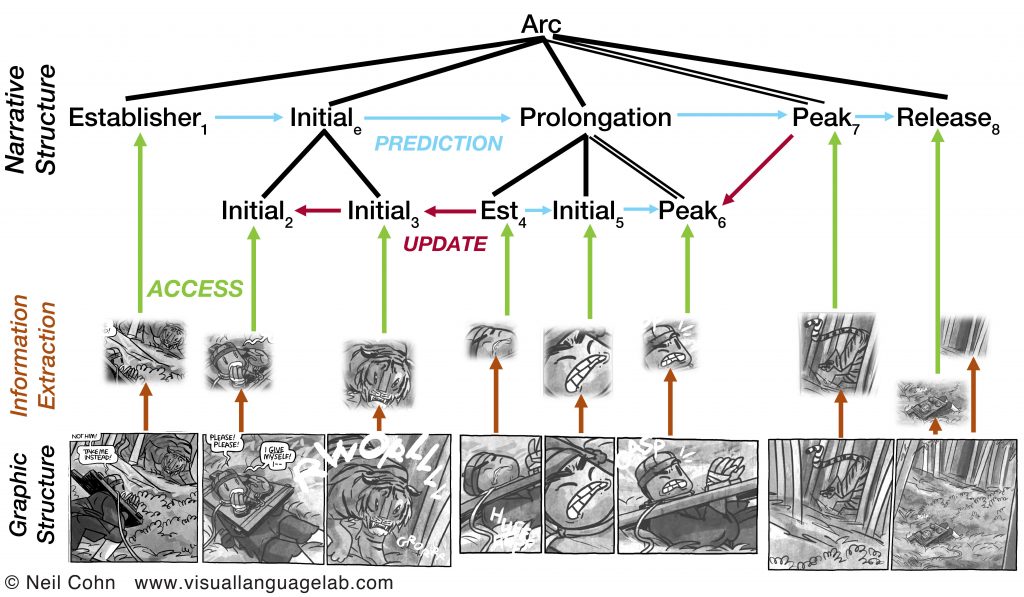

One of the challenges that people often face in using comics as educational material—whether it’s in classrooms, libraries, or other contexts—is that pictures are viewed as simple to understand compared to writing. This leads to the belief that understanding sequential images like comics are easy to understand (see below!), and that sequential images do not involve the kinds of complex cognitive processes involved with reading.

These notions are simply not true.

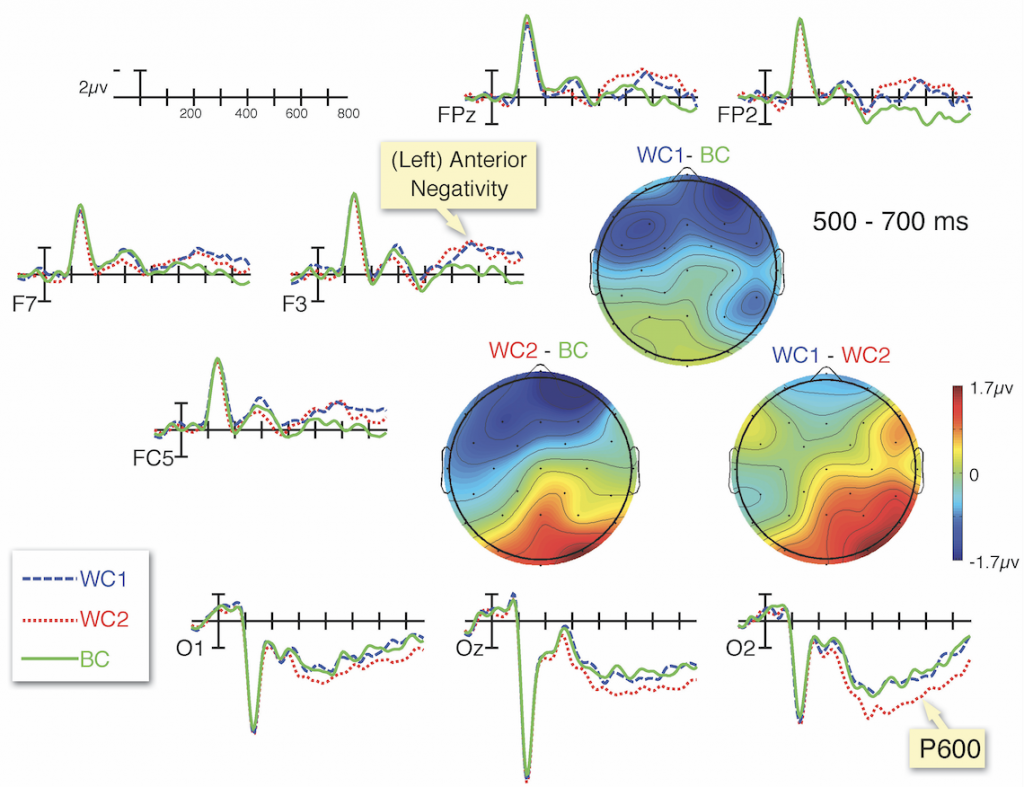

In our studies measuring people’s brains while they read comics, we have observed the same brain responses when people comprehend sequences of wordless images as we see when people read text. Reading comics is reading.

In fact, comics and materials like them are multimodal documents that usually combine text and images. Not only do people use complex cognitive processes in order to read the text and to read the image sequences, but they also need to know how to put them together. In other words, reading comics is actually even more complex than reading text alone.

Expertise

One of the reasons that comics are often thought to be effective for education is because there’s a belief that the images are universal and easy to understand. This assumption often holds that the easy-to-grasp images can help with the understanding of the writing. Unfortunately, this assumption isn’t true.

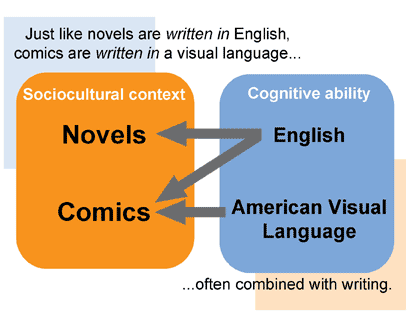

While sequential images can be useful for learning, they also require a fluency to understand. People learn the ability to understand visual languages through exposure and practice with reading comics, just like they need to learn how to understand other languages.

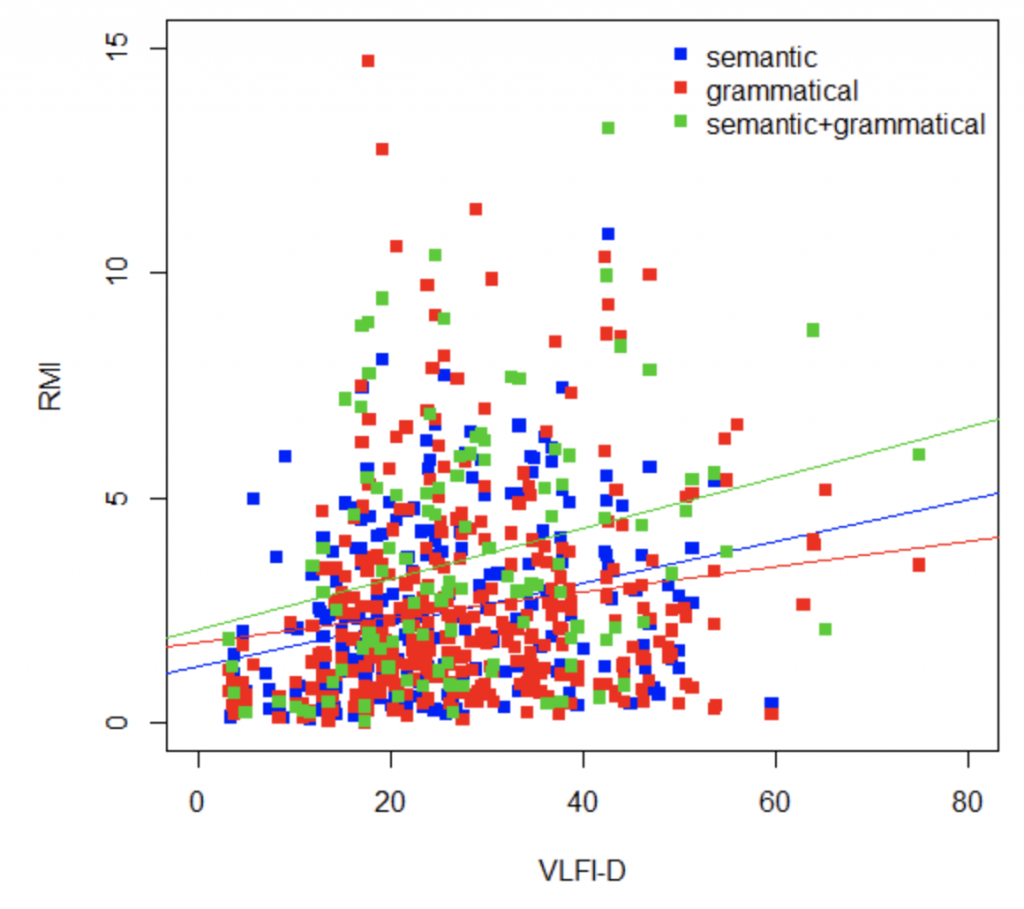

In fact, many studies on comics in education show that the biggest benefits to students come from people who have more comic reading expertise. So, if you’re using comics in educational contexts, it’s important to consider the fluency of your learners, and/or to help them gain that fluency in order to also receive the benefits of using those materials.

Resources

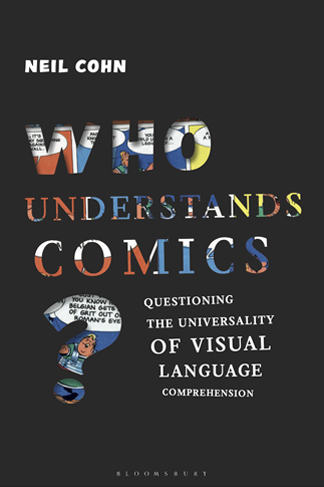

Many of these issues related to comprehension, brain studies, and fluency are discussed in my book, Who Understands Comics?

If you’re doing research about comics in education (or any study measuring comics comprehension), I highly recommend using a measure of comic reading experience. You can find more information on this page.

Reading with Pictures is a non-profit devoted to promoting comics in education, and has many resources on their website.

TrueFiktion is working to develop apps for teaching history through comics.

LingoZING! is an app that uses comics in an engaging interface to teach languages.